Biology professor shares her love of storytelling

Open the door and look around. Let your eyes fall on any of the objects in her small, windowless office: a coyote skull on the shelves to your left, a fossilized chunk of crinoids — a type of aquatic plant — straight ahead, student drawings and paintings of birds lining the walls among numerous other artifacts and ecological memorabilia. Her office is a library in that way, each esoteric object a jigsaw piece in the larger story of life and how biology professor Amy Lewis fits herself into the family of things.

Above all else, Lewis is a storyteller. Point to any object, ask “What’s its story?” and she will tell you.

It’s 1979 in Chatham, New Jersey, and she is sitting cross-legged on the brown and white shag carpet of her family’s den, staring at the tube television from only three feet away. She’s only in fourth grade, but her lifelong hero and biological storyteller David Attenborough fuels her passion for biology and has hypnotized her to the screen. Programs like Attenborough’s 1979 “Life on Earth” and his 1984 “The Living Planet” encouraged Lewis to examine and understand the world she lives in.

Attenborough’s passion for storytelling compelled her to continue to learn more about biology. As a child, she even bought red canvas high tops so she could “be just like him.”

“Anything David did, I found fascinating,” Lewis said. “I’m a biologist because of him.”

There was never a time when Lewis didn’t like reading stories. She would kneel beside her bed or in her middle school library underneath a table, her back to the floor with her feet on the chair’s seat.

But Lewis didn’t quite know the extent of her love for storytelling until her sixth grade teacher, Mrs. Watkins, handed her the right novel. Watkins knew the worlds that would open up to Lewis if only she could just read the right story.

“Take this,” Watkins said standing over her, placing “The Fellowship of the Ring” in her outstretched hands for the first time. “Start with the prologue, then, keep going.”

A week later, Lewis returned to Watkins after reading the first half of the prologue.

“I don’t know if I can do this,” Lewis said.

It was nothing like she had ever read before. It seemed too intricate, too complicated. Watkins told her to keep reading.

“Such was the power of Mrs. Watkins that I did,” Lewis said. “And I was hooked.”

Now, Lewis has read “The Fellowship of the Ring” over 50 times.

Some of her favorite books now include epic fantasy novels by authors like J.R.R. Tolkien, Terry Goodkind, Stephen Donaldson, Lloyd Alexander and Diana Gabaldon.

Lewis’s love for stories goes beyond just reading books, though. She’s been writing a fantasy novel of her own with inspiration from Tolkien.

She enjoys diving into the intricacies of her own characters’ minds more than writing the plot itself. She likes building characters into complex and realistic beings that have a story just like everyone else.

“It’s really a character study,” Lewis said. “I really like to know what’s going on inside [my characters’] heads.”

Reading and writing books aren’t the only ways she has learned to tell stories.

As she grew older, graduating from Chatham Township High School in 1988 and continuing her education in Maine, her desire to learn refused to be quenched.

In the undergraduate program at Bowdoin College, she studied biology and geology in the backwoods of Maine, completing her honors project on tree swallows, a type of small bird.

She wasn’t satisfied. She had to learn more.

She continued her education at Penn State in a Master of Ecology program, researching rufous-sided towhees, another species of bird.

Still, she wasn’t satisfied.

She received her doctorate in wildlife and fisheries science by moving out to South Dakota State University and researching passerines, yet another group of birds, in the sagebrush of western South Dakota, southwestern North Dakota and central Wyoming.

And still, her passion for knowledge couldn’t be limited.

Now, after graduating from SDSU in 2004, she teaches at Augustana University as an assistant professor of biology, telling the story of plants, animals, the world and the forces around them all.

Though most faculty and students consider her the resident ornithologist — an expert of birds — she considers herself an “ecologist who studies birds.”

As a student, Lewis wanted to be a mammalogist, an expert of nonhuman mammals, but she kept getting “diverted into birds,” as she said. During her master’s program, the Four Corners hantavirus broke out in the southwestern United States, putting a halt to her and her professor’s mammal project. She was redirected again at SDSU, where she was assigned to a project researching passerines instead of what she applied for, which was a study of kit foxes.

Lewis is currently a member of the American Society of Mammalogists, and she teaches ornithology at Augustana. During classes, she uses examples of both, from stories of wolves to hummingbirds and everything between.

Her focus is not on the birds or the mammals themselves but about the evolutionary story they tell.

“For a character study, you’re wondering why a person does what they do,” Lewis said. “In biology, you’re wondering why an organism does what it does. In my job, I get to tell the [second] story.”

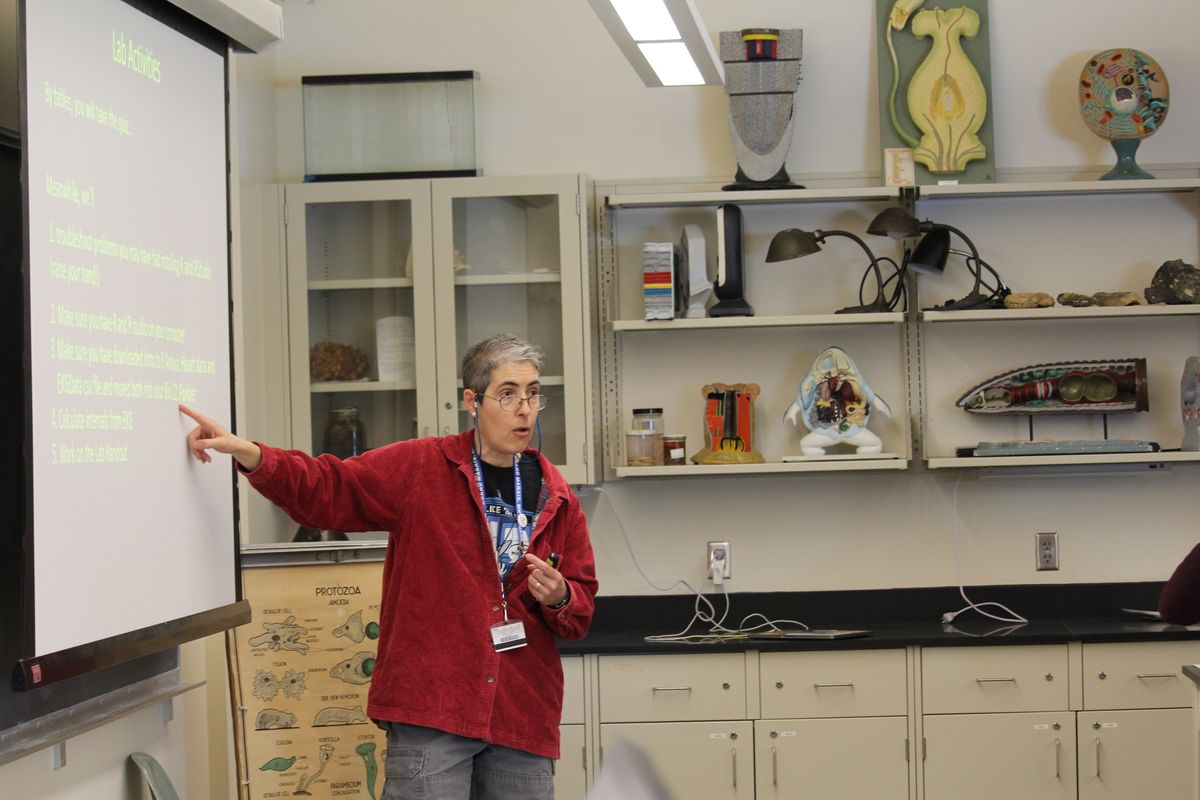

She uses her hands to tell stories. It’s hard not to notice. During her lectures, she looks like a conductor keeping tempo as she bounces from word to word, elucidating the importance of every change in every generation of an evolving species.

Lewis could just stand at the front of the lecture hall and read off her slides, but then she wouldn’t be Amy Lewis, Ph.D., M.S., storyteller extraordinaire. She moves her hands, her feet and her mouth in synchronicity, like the cogs of a storytelling machine.

It’s like she’s hardwired for it. If you didn’t know she was in a lecture hall, you might think she was on television like Attenborough.

Sophomore Heather Howard took Lewis’s introductory biology class her freshman year and recalled one of Lewis’ lectures.

Lewis was teaching about evolution and the ancestors of today’s Homo sapiens. Early humans walked on their knuckles like apes do today, Lewis said. To demonstrate knuckle-walking, she suddenly leapt up onto one of the tables at the front of the hall, pressing the joints of her fingers into its wooden surface.

Her method of teaching is like a boat sailing over choppy seas, her head and her hands bob with emphasis as she swiftly slides across the lecture hall, traveling with her students through a story of her own design. The movement of her hands, her body and her voice — her tone of humbled expertise — tells a story beyond what only words could tell.

Her hero Attenborough said it best: “If you tell a good story, people will hang on to your words.”

In her career, Lewis has focused on ecology: the interactions between organisms and their environment, or the story of biology on planet Earth. Lewis has experienced enough changes firsthand to see how humans have reshaped both the natural world and its fate.

After her trip to the Galapagos Islands in January 2022, she said she was disheartened that a place that’s been preserved for its ecological uniqueness had lost so much.

“It’s a sad story, as is most of ecology,” Lewis said, leaning back in her chair. “It’s a story about humanity, and it doesn’t paint us in a very good light. It’s sort of distressing, but you kind of have to hope, at some point, we’ll figure that out. But getting all eight billion people moving in the right direction is going to be challenging.”

Though the story is an upsetting one, Lewis said, it’s one of the most important.

Lewis referenced a quote that resonated with her from Aldo Leopold — an American naturalist, writer and philosopher.

“Being an ecologist is like walking through a world of wounds,” Lewis said.

But she must do it. Being an ecologist is part of her story.

Lewis sat at her desk looking around at the decorations and gifts in all corners of the room. Statuary birds hang like wind chimes from the ceiling, a Pittsburgh Steelers flag hangs behind her desktop screen, and a pile of assorted documents and books sit firmly beside her clasped hands on the wooden desk.

“I’ve never been the neatest person,” she said, chuckling.

As a child, her desk was often piled high with stuff. As an adult, it seems she hasn’t outgrown the clutter.

Lewis pointed to a painting of a black-and-white warbler that hangs on the right-most side of her office. One of her students painted it for her. Next to it hangs a wooden tree that she made with perches for 12 small brightly colored porcelain birds which another student gave to her.

“I like to show them because I like other people to see my students are so thoughtful,” Lewis said. “It makes me happy. I think it’s really neat that when they see a bird, they think of me.”

Learning how her students work and what in their lives motivates them gets her out of bed in the morning.

The stories of the biological world are a vehicle for Lewis’s storytelling. By teaching students the ecology of life, she is teaching them how every chapter is important to the book of life on Earth. In doing so, she shows students that their story matters too, and the things she teaches become a part of them.

Stories sit on the shelves and tabletops of her office: stories of biology, of the birds in the sky and the animals that walk the ground; stories of fantasy and adventure, swords and sorcery alike; stories of old and stories of new; stories of happiness and stories of great sadness. All of these stories are compiled here, and they tell anyone who may step foot in the space that she has a story as everything else does. And she would like to know yours.

So tell her. Tell her how you fit into the family of things. She will listen.