Artist uses fabric to imitate nature

A video playing on a television illuminates the Eide/Dalrymple Gallery as visitors enter. It shows clips of a forest’s bright, autumn-colored leaves — leaves of honeysuckle yellow, burnt orange, deep burgundy and gold. Tall autumn trees stand against indigo skies, and a crumpled beige leaf floats down to earth.

As a breeze gusts through the canopy, the wooded mountainside fades into darkness, only to rekindle into a new clip with new trees and new colors.

This time, down in the understory, beneath indigo skies and shedding trees, lies blue-dyed, sewn fabric folding across the landscape. It lies over large stones and turned-over logs. Then the video changes again. The wind carries the fabric like a flag, the breeze exerting its full force upon the cloth.

The trees and waving cloth fade to black, and the curtains reopen onto a stark, rocky, California landscape. The blue fabric looks like a mirror reflecting the cerulean sky, and the mountains act as the sky’s frame. Cotton-like clouds float high in the air as the wind relentlessly batters the sewn fabric. It shakes like clothes on a line, but it stays sprawled, solitary.

The clip again fades to black, but this time much slower. It is the end of the seven-minute video stitched together by artist Sandy de Lissovoy, an assistant professor of art at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. The video clips take place in the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia and the High Sierra of California.

The video is an incredible display of nature as artwork. Though the idea of laying fabric across boulders and fallen trees may seem elementary, it is much more profound in practice.

Art is the only medium that gives perspective to the once perspectiveless. In de Lissovoy’s artwork, he uses environmental and political issues to fuel his concept of fabric on earth. It seems that de Lissovoy wants his audience to wonder, “What does it mean?” or “What perspective should I be taking?” Any art piece that holds the viewer, reader or listener to its medium, asking questions, is anything but elementary.

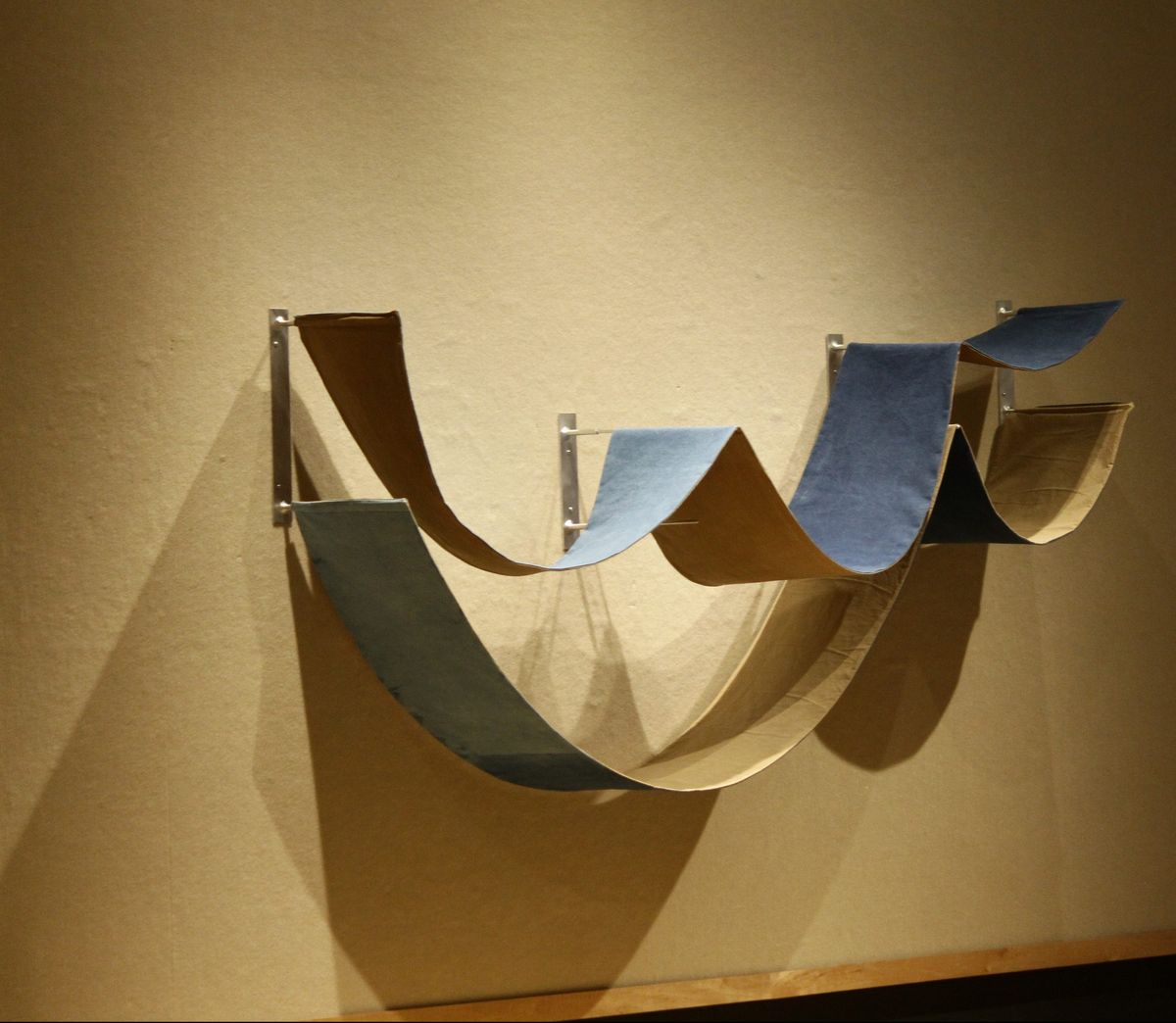

The rest of the gallery contains six sculptures also crafted by de Lissovoy, all as temperamental as an image on the screen. There are fabrics dyed with locally-harvested walnut, indigo, osage orange and tannin dyes. Aluminum tubing holds up the dyed cloth in a conformation resembling the peaks and valleys of mountains.

“My artistic practice is project-based and allows a theme to develop across a body of work and shift across media,” de Lissovoy said in his artistic statement. “I make these forms changeable with aluminum fabricated in the language and function of tent poles and extensions — structural but never permanent.”

As the shape of the indigo fabric resembles mountains, the materials — aluminum tubing and cloth — resemble those one would expect to use while camping. Because this resembles mountains traversed by de Lissovoy, maybe he is trying to show that mountain ranges are as temperamental as tents and sculptures.

Two sculptures stand out in particular. A piece entitled “Sky Topo Extrusion” falls from the rafters like a waterfall, with blue fabric ending in bent ash and white oak that nearly touches the floor. The wood forms a mountain peak that has been lost to surface-mining destruction. The sculpture catches your eye because of its height and because, unlike the other sculptures, it has a wood frame instead of an aluminum one.

The wood frame seems to be much more permanent, mirroring the more permanent consequences of environmental and topographical devastation. De Lissovoy shows that destruction is much more permanent than people think and that our natural wonders are delicate and prone to devastation.

The second piece is entitled “Here: Suspending Color, Falling in Place,” which is also the name of the exhibit.

The sculpture again hangs from the ceiling, but its height isn’t what makes it stand out. The other sculptures are made from blue-dyed fabric on one side and tan-dyed fabric on the other. The sculpture is dyed tan near the peaks of the fabric, and as the fabric falls toward the floor, it becomes a beautiful cerulean.

At the base of the sculpture, rocks lie as if within a riverbed, a gentle stream running overtop of them. Again, aluminum tubing holds it up, and de Lissovoy’s work elucidates the idea of a temperamental natural world.

The collection is abstract, and many of de Lissovoy’s explanations are necessary to understand the artwork. Sculptures, despite having great intent and meaning, can get lost in translation to an untrained eye.

In this collection, de Lissovoy seems to understand that viewers may need a little help. Through video and written word, he explains why the sculptures take the form they do.

The dyed materials are beautiful and contemporary, and they allow viewers to see new perspectives through environmentally rooted materials and artwork.